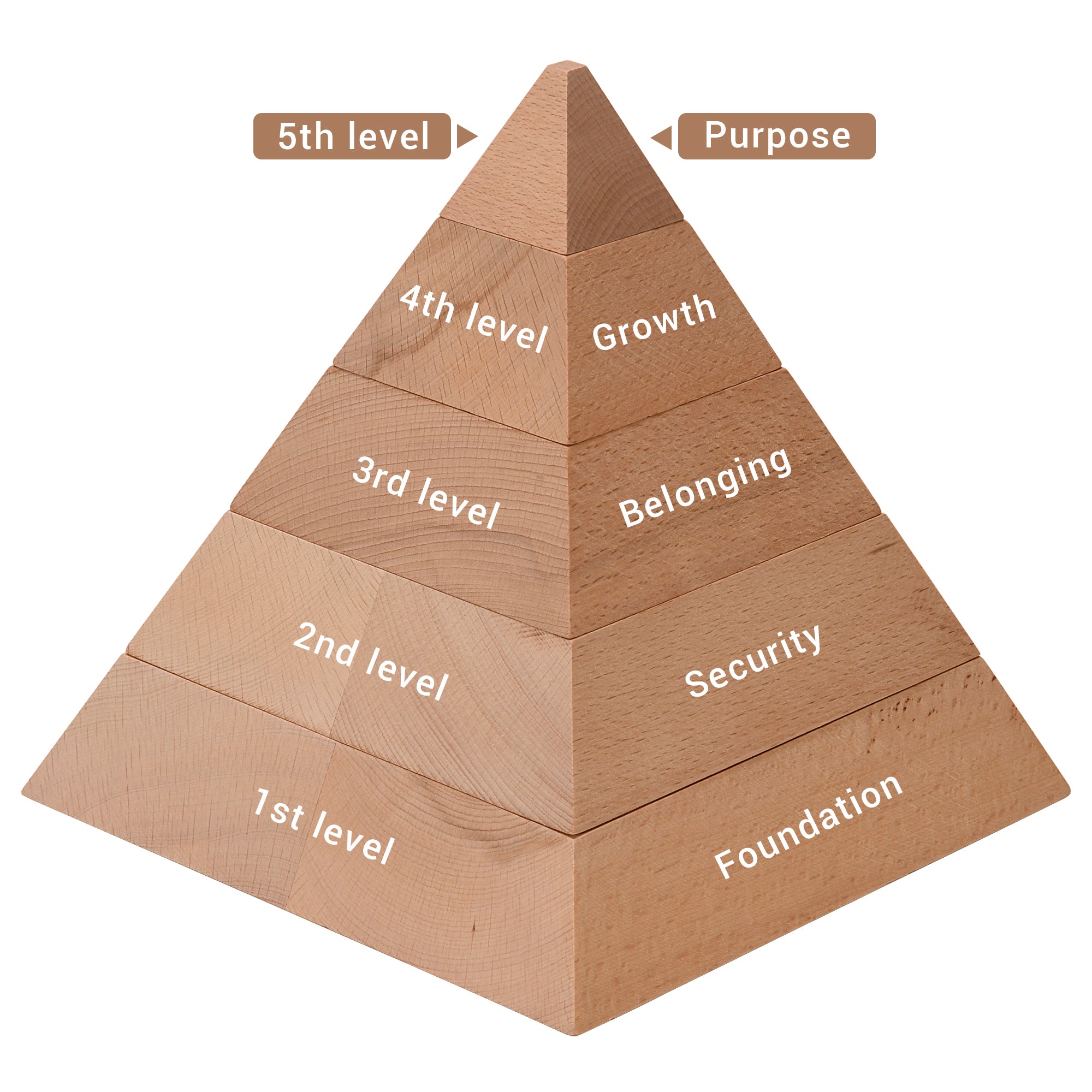

Hardly any other psychological model has become as ingrained in collective thinking as Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs. It's taught in schools, referenced in human resources departments, and frequently used in coaching seminars. However, most of them only scratch the surface—and reproduce assumptions that have little to do with Maslow's actual thinking.

It's time to set the record straight – and to show the potential this model has when used intelligently and with a sense of proportion.

1. “You have to go through the pyramid from bottom to top.”

A common misconception: Only when food, security and social bonding are fully met can one concern oneself with self-realization.

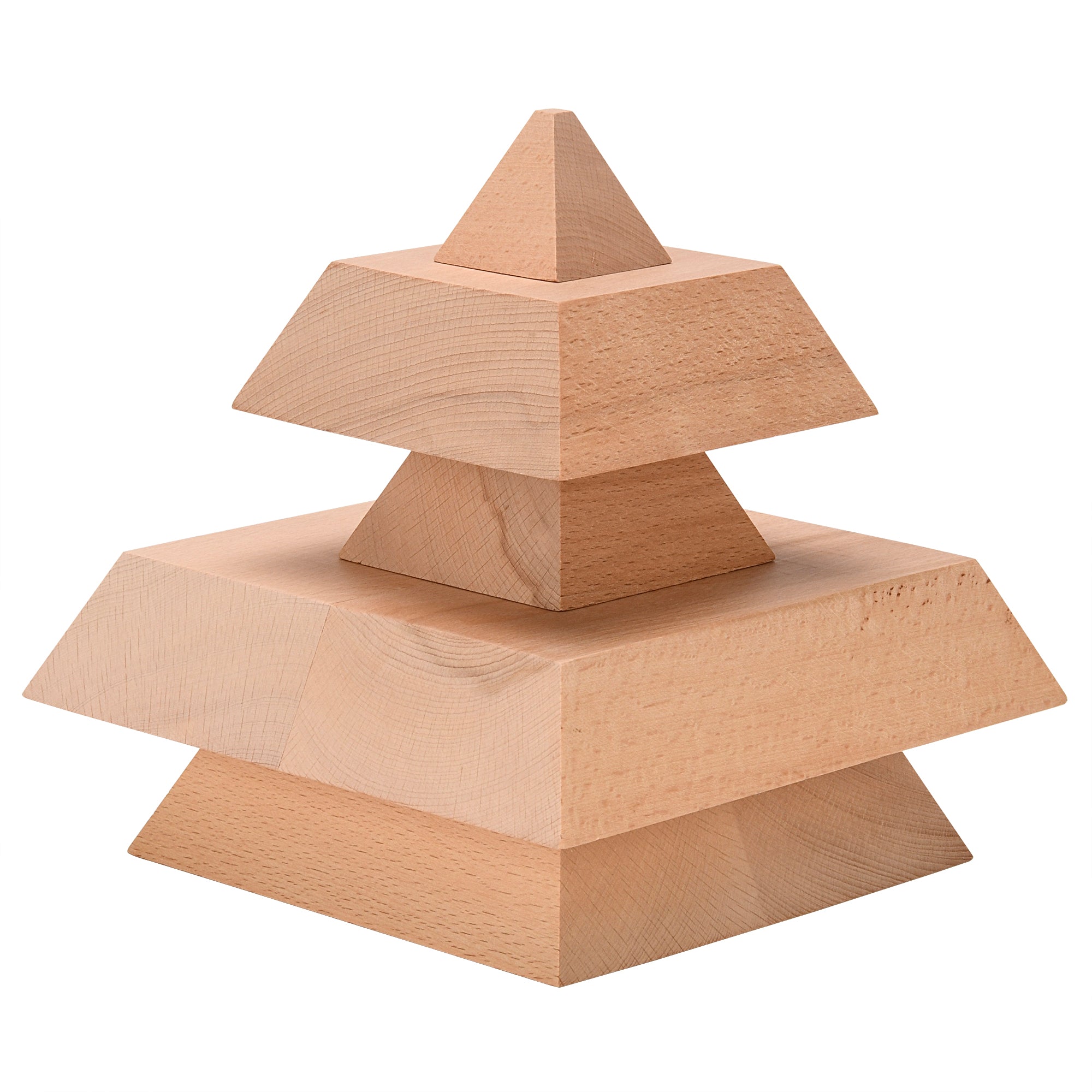

This is a caricature of the original. Maslow spoke of tendencies , not regularities. In reality, people constantly commute between different levels. The pyramid is not an elevator with fixed stops, but a moving structure.

Those who create art in misery, who seek community despite fear, who maintain dignity in chaos – refute the tiered model every day.

What remains? The idea of a hierarchy makes sense—but only as a rough guide, not as a dogma.

2. “The pyramid applies only to the individual.”

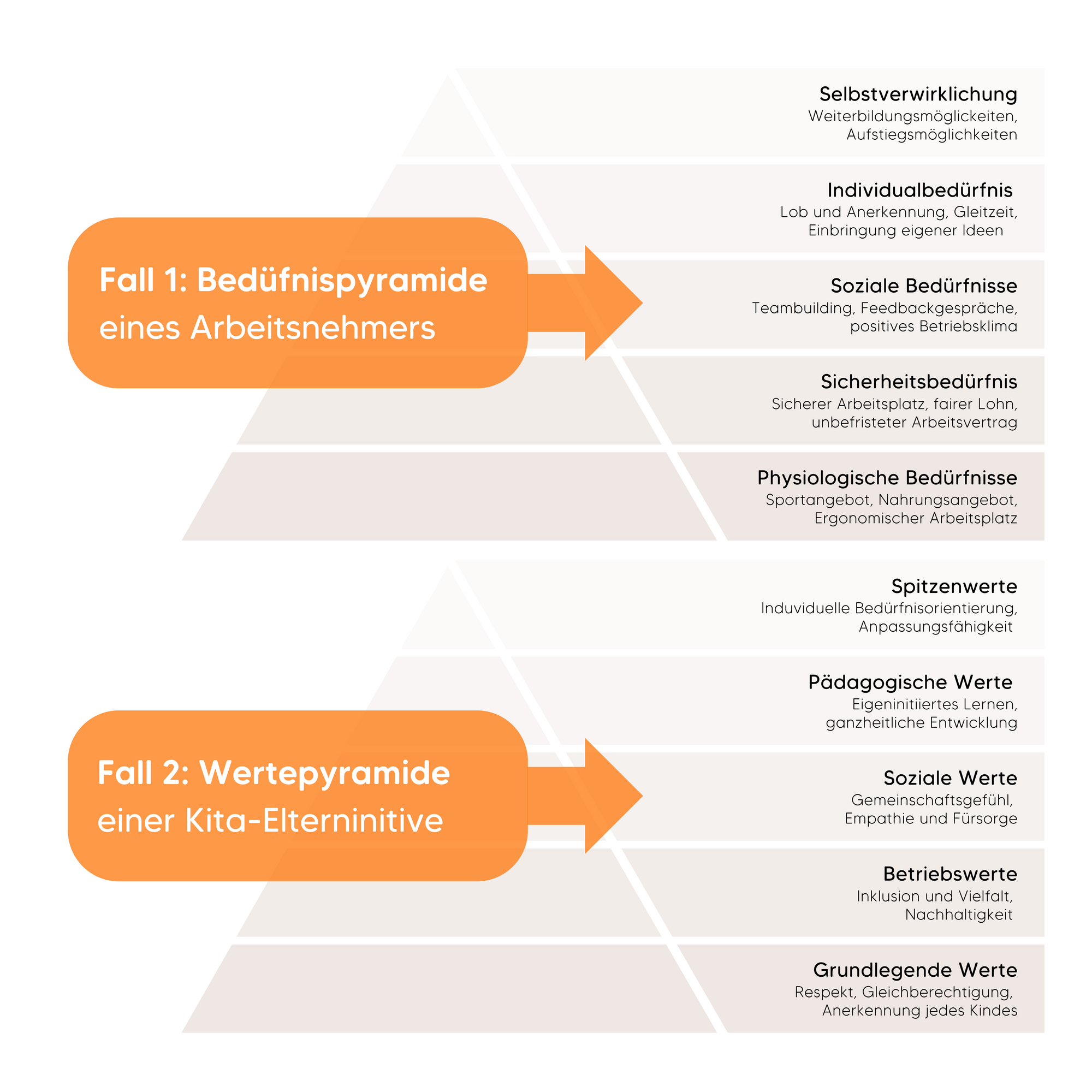

This, too, is a fallacy. The pyramid can be applied to groups, organizations, and even societies.

A team that functions perfectly on the outside can suffer from social disruption on the inside. A society with high levels of prosperity can suffer from a lack of meaning and belonging. Needs are not just individual—they shape systems.

What follows from this? The pyramid is a tool that can be used to visualize not only personal crises but also cultural tensions.

3. “Self-realization is a luxury problem.”

Anyone who believes that self-actualization is only for people with time and money has misunderstood Maslow – or has never experienced what it means to atrophy internally, even though everything on the outside is “right.”

Self-realization is not a bonus at the end of the road, but often the central driving force for development – even under difficult circumstances.

Those who aren't allowed to shape things are managed. Those who can't express themselves eventually fall silent—even to themselves.

Conclusion: The need to create something of one's own is not a luxury. It's part of what defines being human.

4. “The pyramid is outdated.”

Yes, the model dates back to the 20th century. But many of today's alternatives are mere reframings—lacking the elegant core of Maslow's idea.

In addition, Maslow himself later developed the model further, for example to include transcendence – the striving for something greater that goes beyond one’s own self.

In a time of global crises, social fragmentation and constant sensory overload, questions of meaning, connection and orientation are more relevant than ever.

What does this mean? The pyramid isn't outdated—but it demands a new interpretation, beyond PowerPoint slides.

5. “Needs can be planned.”

This is where things get particularly tricky. Many personal development programs suggest that you can manage needs like projects: set goals, allocate resources, and check off the boxes.

But needs don't follow a checklist. They contradict each other, they emerge suddenly, and they can't always be expressed in words.

A person can live in a safe environment on the outside and feel threatened on the inside. They can be part of a group and simultaneously feel isolated.

Insight: The hierarchy of needs is not an Excel model, but an invitation to differentiated self-observation.

Application: What’s the point of all this?

Anyone who works with people—whether in a consulting, teaching, or supporting capacity—needs models. Not as a substitute for experience, but as maps for difficult terrain .

The Maslow pyramid is one such map. It helps identify where someone stands—and what they're looking for . It reveals patterns, identifies deficiencies, and opens up opportunities for discussion.

Whether in individual coaching, team discussions, lessons, or self-reflection: those who use the pyramid not schematically but dialogically gain clarity – about what is supporting and what is missing.

Final thought

Maslow didn't want to lecture. He wanted to understand.

His pyramid is not a dogma, but a model of thought. Not a blueprint, but a compass. Not a tool for optimization, but a mirror for what people need not just to survive—but to live.

If you're willing to look.